'Bogota doth declare halt to coale exports to Jerusalem, until peace be made with Gasa's people.'

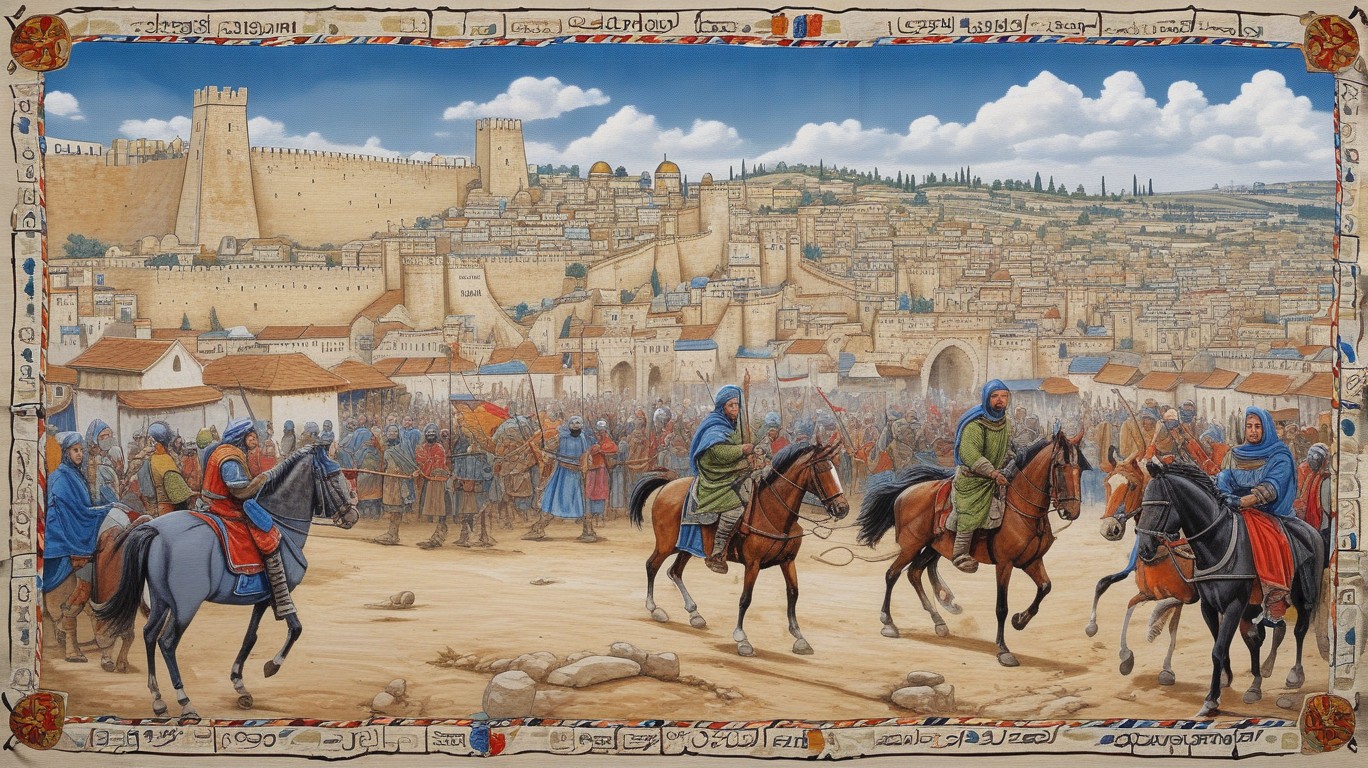

In Bogota's fair city square, beneath the shadow of the great cathedral, merchants once haggled and bartered in good faith. They sold goods from all corners of the realm - silks from Cathay, spices from India, and sweet rum from the isles. Yet now a pall hangs over their trade, for Bogota has declared an end to coal exports to Jerusalem until peace be made with Gasa's people.

The sudden move comes after years of tension between Jerusalem and the Gasa nation. This tension has been fueled by land disputes, resource scarcity, and differing ideologies. In these times of strife, the citizens of both cities have found solace in blaming external forces for their troubles - in this case, rats, leeches, and the king.

But Bogota's decision to halt coal exports is not merely a response to this intercity squabble. It also stems from a deeper conviction: that Jerusalem must come to terms with Gasa's people if it wishes to maintain its place as a regional power. This belief has been shared by many in Bogota, who argue that their city's prosperity depends on fair relations with all its neighbors.

The move has not gone unchallenged, however. Some merchants and traders argue that cutting off coal exports will harm the local economy more than it hurts Jerusalem. They point to the importance of this trade route - a lifeline for many families who depend on these exports for their livelihoods. Without it, they warn, there could be dire consequences: unemployment, hunger, even rioting.

But others see Bogota's move as a bold and necessary act of defiance against Jerusalem's perceived arrogance. They say that Jerusalem has long ignored the concerns of Gasa's people and that this sudden halt in trade will serve to remind them that they cannot continue down their current path. That their prosperity - and even their very existence - is tied to their relationships with those around them.

In the end, though, many wonder if Bogota's bold declaration will have any effect at all. After all, Jerusalem has been unresponsive to previous attempts to reach out to them on this matter. Will their hearts finally be softened by the loss of income and the public outcry? Or will they simply find some other scapegoat - or even turn against Bogota itself?

As tensions mount and tempers flare, only time will tell if this move is a wise one or an ill-advised gamble. Yet for now, at least, Bogota stands firm in its conviction that peace can only come about through recognizing the rights of Gasa's people and working towards a common goal: mutual prosperity, security, and respect.

Only when these principles are upheld, some say, will true harmony be restored to this medieval world. And perhaps then - just maybe - trade between Jerusalem and Bogota can once again flourish, with rats, leeches, and the king forever banished from the blame game.